The Last Lions of Asia:

Can One Forest Hold Their Future?

- Author: Sean Verdi

- Publication Date: July 31, 2025

- Focus Species: Panthera leo (Lion)

As the Asiatic lion population in Gujarat’s Gir Forest continues to grow, these rare big cats are expanding beyond park boundaries into agricultural fields and villages. While this could be a sign of recovery, how these successes are balanced with new threats such as disease outbreaks and habitat encroachment, highlights the urgent need for a second population beyond Gir.

Once kings of a range that stretched from the Mediterranean to India’s beating heart, the Asiatic lion now persist in just one corner of the subcontinent. Fewer than 700 remain in the wild, all of them clustered in and around Gir National Park, which is critical habitat for this species but where human-wildlife conflict persists.

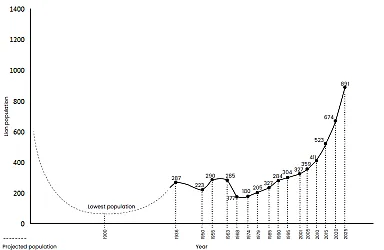

The recovery of the Asiatic lion is one of conservation’s quieter success stories. In the early 20th century, relentless hunting and habitat loss reduced the population to a mere dozen individuals. Today, that number has climbed to over 700, thanks to decades of protection by local communities, forest authorities, and conservationists. According to the 2025 census by the Gujarat Forest Department, the lion population rose from 674 in 2020 to 891 in 2025, a remarkable 32.2% increase in just five years.

A recent study by Singh et al 2025 J. Wildlife Sci. illustrates the projected population trend for Asiatic lions since 1900.

Although lion numbers have grown, the space they inhabit remains dangerously small. Gir and its surrounding landscapes support the entire global wild population, which makes these lions uniquely vulnerable to localized threats. A disease outbreak like that of canine distemper virus (CDV) in 2018 that killed over 20 lions could have devastating consequences. Similarly, wildfires and ongoing human encroachment could have similar effects. As lions increasingly venture beyond the park’s boundaries, conflict with humans (e.g., livestock depredation), as well as retaliatory killings, and vehicle collisions are inevitable.

Scientists have long warned that concentrating the entire Asiatic lion population in one place creates an ecological bottleneck. Genetic studies reveal that these lions suffer from extremely low diversity, with heterozygosity at just ~25%, likely reflecting historic bottlenecks as much as recent decline. This lack of genetic variation corresponds with documented reproductive health concerns, including abnormal sperm morphology and limited immune gene diversity, increasing the risk of inbreeding and disease vulnerability.

To address this, in 2013, India’s Supreme Court ordered that a second population be established in Kuno National Park, Madhya Pradesh. But more than a decade later, no lions have been introduced there. Political resistance and state-level disagreements have delayed the translocation. Still, hope remains. The cultural reverence for lions among many in Gujarat, particularly the local Maldhari herdsmen who share the land contributes to coexistence.

Ensuring the long-term survival of the Asiatic lion will require more than just population estimates. A multi-pronged conservation approach is needed, including expanding suitable habitat beyond Gir, establishing a genetically viable second population, mitigating human-lion conflict via improved livestock protection, and continuing to engage local communities who share the land with this species. With disease, habitat pressure, and genetic bottlenecks looming, the future of the Asiatic lion depends on protection and on strategic, evidence-based resilience planning.

References

Banerjee, K., Jhala, Y.V., Chauhan, K.S. and Dave, C.V., 2013. Living with lions: the economics of coexistence in the Gir forests, India. PLoS One, 8: e49457.

Dharmakumarsinhji, R.S. The Gir Lions: Panthera Leo Persica. 2012. https://www.sanctuarynaturefoundation.org/article/the-gir-lions%3A-panthera-leo-persica. Sanctuary Nature Foundation.

Gogoi, K., Banerjee, K., Chakrabarti, S., Singh, A.P. and Jhala, Y.V. 2025. Deciphering the enigma of human− lion coexistence in India. Conservation Biology, 39: e14420.

Jhala, Y.V., Banerjee, K., Chakrabarti, S., Basu, P., Singh, K., Dave, C. and Gogoi, K. 2019. Asiatic lion: Ecology, economics, and politics of conservation. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 7: 312.

Mourya, D.T., Yadav, P.D., Mohandas, S., Kadiwar, R.F., Vala, M.K., Saxena, A.K., Shete-Aich, A., Gupta, N., Purushothama, P., Sahay, R.R. and Gangakhedkar, R.R. 2019. Canine distemper virus in Asiatic lions of Gujarat State, India. Emerging infectious diseases, 25: 2128.

Singh, H.S. 2025. Arrival, rise, fall, and again rise of the asiatic lion Panthera Leo Leo in India, Journal of Wildlife Science. https://jwls.in/bhuu5534/

Do You Have 2-4 Hours A Month To Preserve Your Local Ecosystem?

Our volunteers are the driving force behind making true change in ecosystem health and wild cat conservation. Some like to volunteer in the field, others help us maintain our online presence, and some work with events. With just a few hours a month, you can make a difference, too.

Make A Difference Right Now

As a 501(c)3 nonprofit, our work is only possible because of generous donors like you.

More than 90% of your donation will go directly to our groundbreaking research, outreach, and education programs.

This is where true change starts. If you’d like to be a part of it, make a donation to Felidae Conservation Fund today:

Or,