Mercury in the Mists:

How Bay Area fog may carry mercury to coastal pumas

- Author: Kristine Piedad

- Publication Date: December 08, 2023

- Focus Species: Puma concolor (Mountain Lion)

Mercury in the Mists: How Bay Area fog may carry mercury to coastal pumas

California’s Bay Area is notorious for its heavy fog, whose billowing white clouds envelop the coast and the surrounding hills. These fogs are an important part of the surrounding ecosystems, with redwoods receiving as much as 30-40% of their water intake from fog during drier seasons. Fog plays a critical role in regulating temperatures, preventing both frosts and wildfires throughout the year. However, research suggests that fog may also play a part in increasing the levels of mercury, a potentially deadly heavy metal, in terrestrial species, such as the puma.

Mercury is naturally released into the environment by numerous natural geologic forces, such as volcanoes and geothermal springs. However, since around 1500 C.E., humans have increased the levels of atmospheric mercury sevenfold. Mercury also enters the watershed, with levels in the ocean having increased by 10% since before the industrial revolution. Mercury levels in the top one hundred meters of water have tripled. Atmospheric mercury is most often in an inorganic form, but within aquatic systems inorganic mercury is converted to organic mercury, which can be easily taken up by life forms and is considered the most dangerous form of mercury. Mercury is a major source of concern for many aquatic ecosystems, in salt- and freshwater systems. There is growing evidence suggesting it is a concern for terrestrial ecosystems as well. A 2019 study suggests that the Bay Area’s famous fog, formed from the mercury heavy top layers of the ocean, carries the mercury from the ocean and deposits it on land, where plants uptake it and it enters the food web.

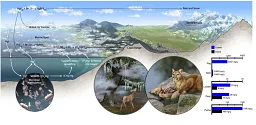

From: Weiss-Penzias, P. et al. 2016. Total- and monomethyl-mercury and major ions in coastal California fog water: Results from two years of sampling on land and at sea. Elem. Sci. Anthr. Included in Weiss-Penzias 2019. Caption: "Conceptual diagram showing the hypothesized sources and mechanisms of transfer of organic Hg species from the ocean to the coastal terrestrial food web in central California, USA. Bar charts indicate the mean concentrations of MMHg observed in this work plus fog and rainwater concentration".

The study measured mercury levels in areas affected by Bay Area fog compared to mercury levels of organisms farther inland. Mercury levels were measured in organisms in three different tiers of the food chain: lichen, deer, and pumas. Lichen do not have roots, meaning it must absorb nutrients and contaminants through the atmosphere. As a result, it can be used as a bioindicator of atmospheric pollutants. Lichen taken from areas affected by Bay Area fog had significantly higher levels of mercury compared to inland lichen. The same was true for deer, which consume lichen. Pumas in the affected areas had mercury levels three times higher than those of deer from inland California. Bay Area pumas do not eat much food from aquatic sources, unlike Florida pumas, and instead eat primarily deer, which in turn eat terrestrial plants. The terrestrial diets of the Bay Area pumas and deer suggest the mercury in their bodies originally comes from terrestrial plants, such as lichen, rather than from aquatic species. The fog serves as the missing link—the mechanism that moves aquatic mercury into the terrestrial ecosystem. While the mercury levels in the fog are not high enough to make walking in it a danger to humans, if current trends continue, significant damage might be done to nearby ecosystems.

When lichen, and other affected plants, are eaten by herbivores, such as deer, the mercury begins its journey up the food chain. Mercury is a bioaccumulator and is absorbed more quickly than the body can get rid of it. Bioaccumulation refers to the process by which a contaminant accumulates in organisms over time, and this is magnified in organisms toward the top of the food chain. In this simplified food chain, lichen absorbs mercury from the fog, deer absorb mercury from the lichen, and pumas absorb the mercury from the deer they eat. Mercury concentrations can increase by 1,000 times from the bottom to the top of the food chain, making it a real threat to the conservation and well-being of large predators.

As global mercury levels continue to rise, it is a serious concern for global ecosystems. Mercury causes many health issues and is considered a neurotoxin. High concentrations of mercury harm many parts of the body. Mercury can cause brain damage and affect fertility. Mercury widely disperses from its original source, making targeting of its producers difficult, but the top human-caused sources of mercury are artisanal and small-scale gold mining, accounting for 37.7% of mercury emissions in 2015, and stationary coal combustion (21%). In order to preserve the health of ecosystems around the world, particularly that of apex predators like pumas, it is essential that international bodies cooperate to limit mercury emissions.

References

Burrows, L. (2023, November 1). Human emissions increased mercury in the atmosphere sevenfold. Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. <https://seas.harvard.edu/news/2023/11/human-emissions-increased-mercury-atmospheresevenfold>

Dybas, C., & Murphy, S. (2014). Mercury in the world’s oceans: On the rise. NationalScience Foundation. <https://www.nsf.gov/news/news_summ.jsp?cntn_id=132171>

Hong, Y.-S., Kim, Y.-M., & Lee, K.-E. (2012). Methylmercury exposure and health effects. Journal of Preventive Medicine; Public Health, 45(6), 353–363.

Katz, B. (2019, December 2). Mercury-laden fog may be poisoning California’s Mountain Lions. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/mercuryladen-fog-may-be-poisoning-californias-mountain-lions-180973677/

Luis, N., & Saifee, A. T. (2022, November 22). Marin Voice: There are consequences to less Bay Area fog caused by human impacts on climate. Marin Independent Journal. <https://www.marinij.com/2022/11/24/marin-voice-there-are-consequences-to-less-bayarea-fog-caused-by-human-impacts-on-climate/Mercury>

Environmental Protection Agency. (2023) .https://www.epa.gov/international-cooperation/mercury-emissions-global-contextMercury.

U.S. Geological Survey. (2019). https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/waterresources/science/mercury

Reyes-Velarde, A. (2019, December 2). Coastal fog linked to mercury poisoning in Mountain Lions, researchers say. Los Angeles Times. <https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2019-12-02/mountain-lions-in-coastal-regionshave-high-mercury-levels>

Tolmé, P. (2012, November 7). Mercury’s harmful effects. National Wildlife Federation. <https://www.nwf.org/Magazines/National-Wildlife/2013/DecJan/Conservation/Mercuryand-Wildlife>

Weiss-Penzias, P. S., Bank, M. S., Clifford, D. L., Torregrosa, A., Zheng, B., Lin, W., & Wilmers, C. C. (2019). Marine fog inputs appear to increase methyl mercury bioaccumulation in a coastal terrestrial food web. Scientific Reports.

Do You Have 2-4 Hours A Month To Preserve Your Local Ecosystem?

Our volunteers are the driving force behind making true change in ecosystem health and wild cat conservation. Some like to volunteer in the field, others help us maintain our online presence, and some work with events. With just a few hours a month, you can make a difference, too.

Make A Difference Right Now

As a 501(c)3 nonprofit, our work is only possible because of generous donors like you.

More than 90% of your donation will go directly to our groundbreaking research, outreach, and education programs.

This is where true change starts. If you’d like to be a part of it, make a donation to Felidae Conservation Fund today:

Or,